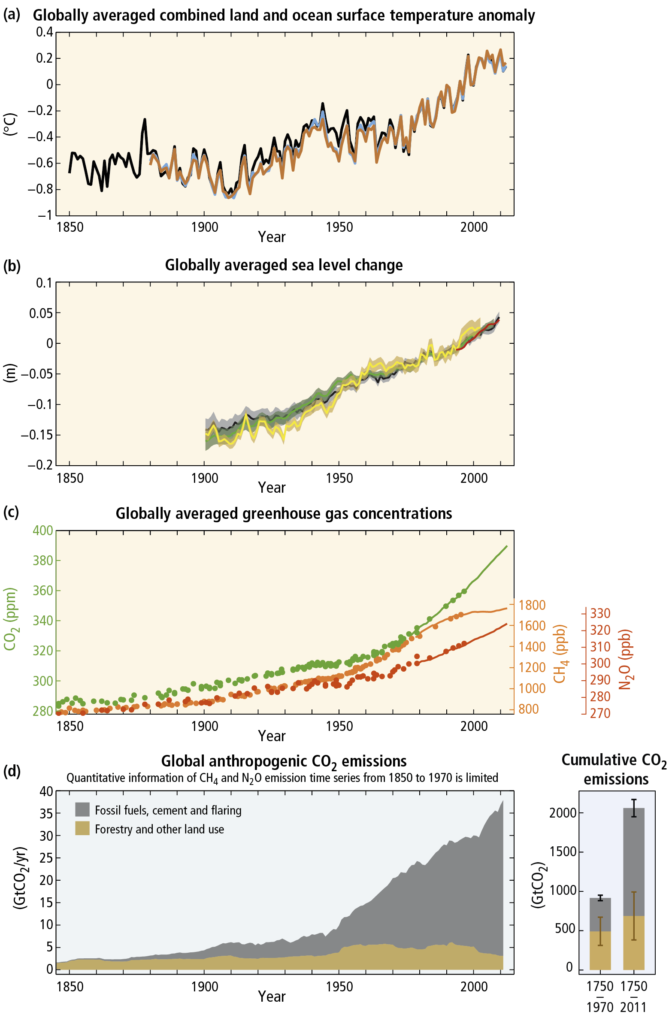

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Fifth Assessment Report affirms that “warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice and rising global average sea level.”[1] Researchers have made progress in their understanding of how the Earth’s climate is changing in space and time through improvements and extensions of numerous datasets and data analyses, broader geographical coverage, better understanding of uncertainties and a wider variety of measurements.[2] These refinements expand upon the findings of previous IPCC Assessments – today, observational evidence from all continents and most oceans shows that “regional changes in temperature have had discernible impacts on physical and biological systems.”

Figure A1: Observations and other indicators of a changing global climate system[3]

In short, the Earth is already responding to climate change drivers introduced by mankind.

Temperatures and Extreme Events are Increasing Globally

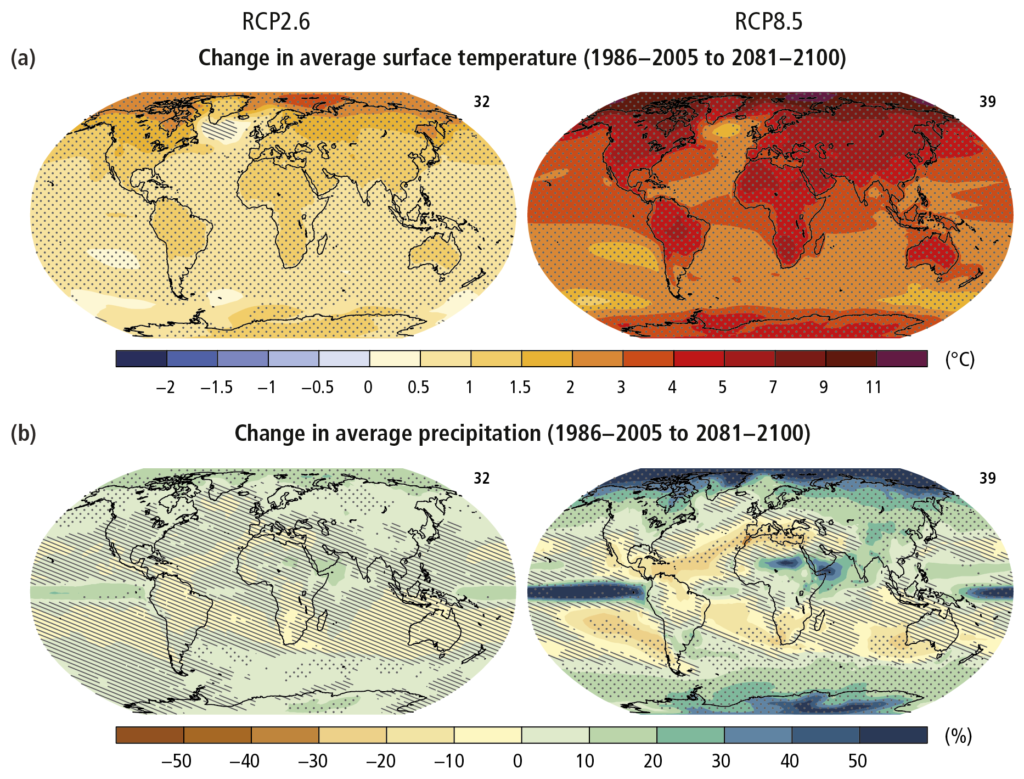

Figure A2: Change in average surface temperature (a) and change in average precipitation (b) based on multi-model mean projections for 2081–2100 relative to 1986–2005 under the RCP2.6 (left) and RCP8.5 (right) scenarios.

Surface temperature is projected to rise over the 21st century under all assessed emission scenarios. It is very likely that heat waves will occur more often and last longer, and that extreme precipitation events will become more intense and frequent in many regions. The ocean will continue to warm and acidify, and global mean sea level to rise. Changes in many extreme weather and climate events have been observed since about 1950. Some of these changes have been linked to human influences, including a decrease in cold temperature extremes, an increase in warm temperature extremes, an increase in extreme high sea levels, and an increase in the number of heavy precipitation events in a number of regions.[4]

Climate Risks

Climate change is expected to cause significant negative effects on food security. Due to projected climate change by the mid-21st century and beyond, global marine species redistribution and marine biodiversity reduction in sensitive regions will challenge the sustained provision of fisheries productivity and other ecosystem services. For wheat, rice and maize in tropical and temperate regions, climate change is projected to negatively impact production under local temperature increases of 2°C or more above late 20th century levels, although in some cases individual locations may benefit. Global temperature increases of ~4°C or more above late 20th century levels, combined with increasing food demand, would pose drastic risks to food security globally. Climate change is projected to reduce renewable surface water and groundwater resources in most dry subtropical regions, intensifying competition for water among sectors.

Until mid-century, projected climate change will impact human health mainly by exacerbating health problems that already exist. Throughout the 21st century, climate change is expected to lead to increases in ill-health in many regions, particularly in developing countries. Health impacts include greater likelihood of injury and death due to more intense heat waves and fires, increased risks from foodborne and waterborne diseases and loss of work capacity and reduced labor productivity in vulnerable populations. Risks of undernutrition in poor regions will increase. Risks from vector-borne diseases are projected to generally increase with warming, due to the extension of the infection area and season, despite reductions in some areas that become too hot for disease vectors.

In urban areas, climate change is projected to increase risks for people, assets, economies and ecosystems, including risks from heat stress, storms and extreme precipitation, inland and coastal flooding, landslides, air pollution, drought, water scarcity, sea level rise and storm surges. These risks are amplified for those lacking essential infrastructure and services or living in exposed areas. Rural areas are expected to experience major impacts on water availability and supply, food security, infrastructure and agricultural incomes, including shifts in the production areas of food and non-food crops around the world.

Climate change is projected to increase displacement of people. Populations that lack the resources for planned migration experience higher exposure to extreme weather events, particularly in developing countries with low income. Climate change can indirectly increase risks of violent conflicts by amplifying well-documented drivers of these conflicts such as poverty and economic shocks.[5]

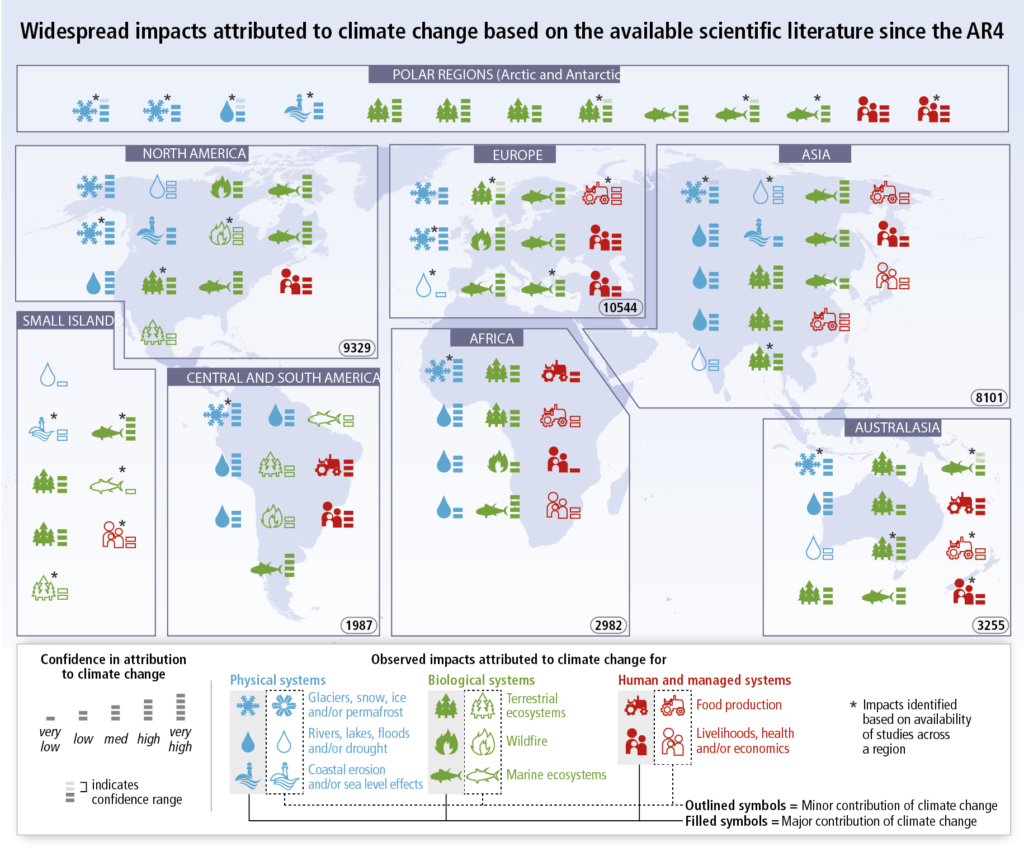

Regional and Local Impacts

Because the impacts of climate change vary geographically, it is important to know what effects are specifically expected for your corner of the globe.

Figure A3: Climate impacts around the world. Symbols indicate categories of attributed impacts, the relative contribution of climate change (major or minor) to the observed impact and confidence in attribution.

Numbers in ovals indicate regional totals of climate change publications from 2001 to 2010, based on the Scopus bibliographic database for publications in English with individual countries mentioned in title, abstract or keywords (as of July 2011). These numbers provide an overall measure of the available scientific literature on climate change across regions; they do not indicate the number of publications supporting attribution of climate change impacts in each region. Studies for polar regions and small islands are grouped with neighboring continental regions.[6]

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. It may not be used for any commercial purpose. Any non-commercial use of this material must provide attribution to ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability USA.

===============================================================================

[1]. IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K Pachauri, and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp

[2]. IPCC, 2014: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M.Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

[3]. IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K Pachauri, and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp

[4]. IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K Pachauri, and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp

[5]. IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K Pachauri, and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp

[6]. IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K Pachauri, and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp